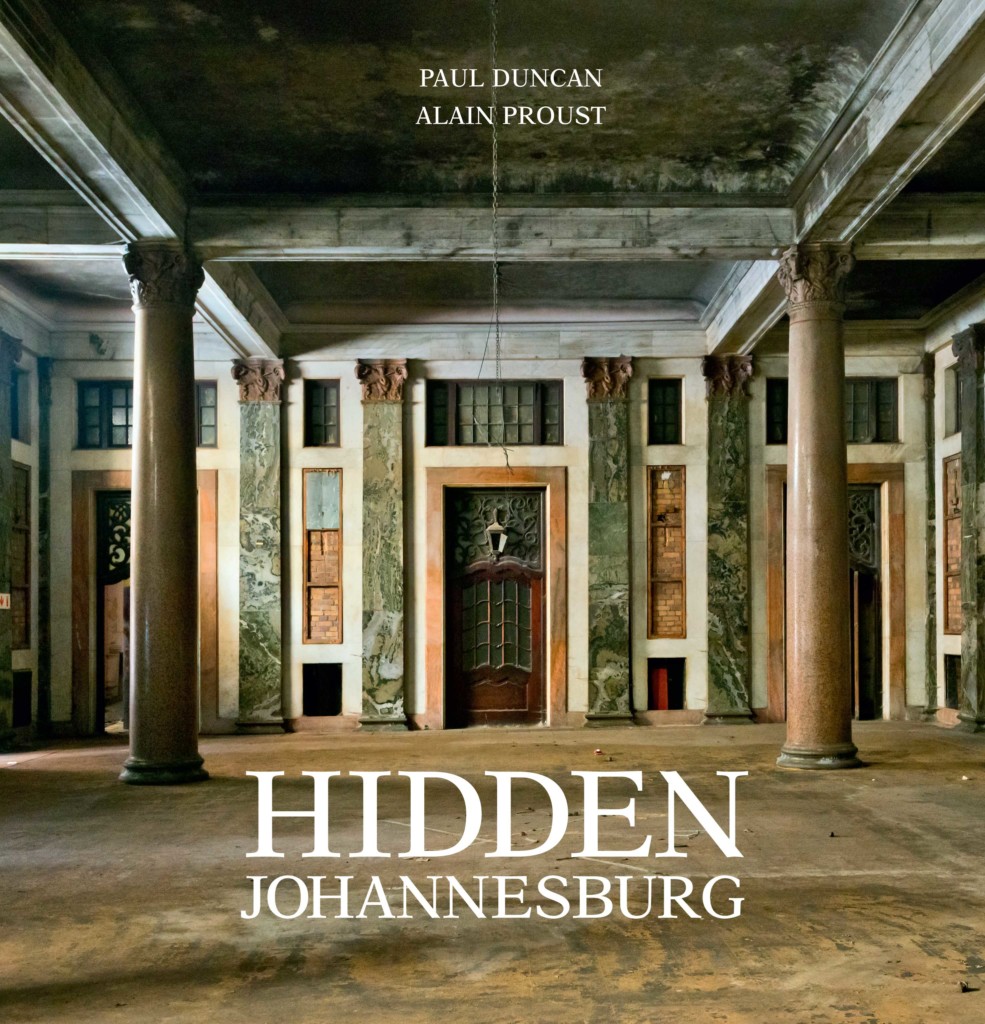

Paul Duncan’s must-have reference book ‘Hidden Johannesburg’, with photographs by Alain Proust, reveals many secrets of the city’s gold mining past and rich architectural heritage. Using Duncan as our guide we have picked out ten spaces of his Hidden Johannesburg that give a sense of the city’s social and architectural history.

Visiting Joburg for its history is like attending a peepshow; the tantalizing glimpses are never as satisfying as they should be. Rapid changes in the city’s short 130-year history have meant that the cityscape’s appearance never tells the full story. You still have to dig to uncover gold here.

In his lavish and highly collectable book Duncan describes Joburg as “a city plonked down and grown like some hybrid maverick in the hot African veld”. With plenty of land and mining wealth from its founding (1886) Johannesburg was able to quickly construct its way from shacks and shanties to an extraordinary array of architectural styles, from fin de siècle to Beaux-Arts, Arts and Crafts to neoclassical.

Duncan writes: “Johannesburg has been in a constant state of reinvention as long as it’s been in existence” and through it all the city has always “pretended to be cosmopolitan”. His quest was to rediscover buildings of great architectural beauty or significance. In some ways what is not visible strongly defines the city than what is visible. This only contributes to the sense of adventure for exploring many repurposed spaces.

The Old Fort (1896)

Built by the ZAR Republic, the British took control of the fort following the Jameson Raid, and used it as a prison from 1899. The impressive crenellated entrance and bastions with gun emplacements were never used to defend the city. Instead the site became a prison for common criminals and increasingly, following the 1952 Defiance Campaign, political prisoners. Among its former occupants were Gandhi, and remarkably two Nobel peace-prize winners Nelson Mandela and Albert Luthuli. The prison was shut in 1983 and the Old Fort is now part of the impressive Constitution Hill complex.

The View (1896)

One of Johannesburg’s oldest surviving houses, this Victorian mansion is remarkable for its exquisitely restored interiors and former owner. From 1903 Sir Thomas Cullinan lived here with his family. A bricklayer-turned prospector his Premier Diamond Mine entered the history books with the discovery of the Cullinan Diamond, the world’s largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found, now part of the British Crown Jewels. Since 1976 the house has served as the Transvaal Scottish Regiment headquarters. Ridge Rd, Parktown.

Corner House (1903)

This elegant building by Leck & Emley built on Commissioner Street, a main thoroughfare of early Johannesburg, started life as an iron-roofed wooden shack. It became the seat of the company that once controlled the world’s richest gold mines and Johannesburg’s first ‘skyscraper’. Among its many striking features is its opulent staircases, the red-brown cut stone of its exterior, corner turrets and copper-clad projecting central bay that runs vertically up the ten-storey building. Today the building houses law firms and a coding school and is the head office for Urban Ocean property developers. 44 Main St, Marshalltown, City Centre.

Rand Club (1904)

Once the centre of Johannesburg’s powerful mining world this exclusive member’s club – to which women were only admitted in 1993 and people of colour post-1994 – today is reinventing itself for a city no longer dependant on mining wealth. While the club first opened in 1887 the current building, its third, was designed by Leck & Emley who transformed the small brick structure into a four-storey Beaux-Arts edifice with a steel frame imported from Glasgow. The interiors that includes a sweeping staircase and impressive glass dome, the 103-foot long teak bar, billiards room, ball room and the member’s-only library have been exquisitely maintained and a visit can’t but not conjure up the once gloriously affluent mining past. Cnr of Fox and Loveday Sts, Marshalltown

Northwards (1904)

Designed by Herbert Baker this 40-room mansion built from local quartzite was one of many designed for the wealthy Randlords who escaped the mining dust to the city’s ridges seeking fresh air. Northwards was home to one of Joburg’s most flamboyant socialites, Josie Dale Lace (her parents named her Josephine Brink and she was born in the Karoo). Legend has it she travelled around Johannesburg in a zebra-drawn carriage. Elements of English design and architecture mix with Cape Dutch features to produce a spectacular property with a double-volume ballroom, Palladian windows and elaborate gables. The house is now owned by the Northwards Trust. Rockridge Rd, Parktown.

Villa Arcadia (1909)

Designed by Herbert Baker and built in 1909 from indigenous materials this stately Italianate mansion overlooked the forest that was in place of what is now suburban Saxonwold. This was the home of mining magnate and politician Sir Lionel Phillips and his wife Lady Florence Phillips, to whom the city owes a great cultural debt. Lady Phillips was a tireless advocate for the arts and founded the Johannesburg Art Gallery. She discovered the piece of land on which the house came to stand while out horseriding, leaving the dusty gold mining heart of the city for the nearby Parktown Ridge. The house has had an interesting history. After the Phillips family moved out Villa Arcadia was bought for use as a Jewish orphanage and operated as such for many years until its sale to Hollard Insurance Company, who in a fitting tribute to Lady Phillips completed a magnificent restoration and have filled it with some of the pieces of the company’s vast contemporary art collection. Oxford Rd, Parktown.

Satyagraha House (1908)

The two simple thatch-roofed rondawels called The Kraal, that were once home to Mahatma Gandhi, are today part of a seven-room guesthouse decorated with furniture and objects sourced from Gandhi’s Indian home state of Gujarat. They were designed by German architect and body-builder Herman Kallenbach and the pair lived here from 1908 to the end of 1909. This modest location, which today still emits a sense of tranquillity, is the place where Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent resistance Satyagraha (derived from a Sanskrit word) was formulated, a movement that shook the world. Owned by French Company Voyageurs du Monde the museum is open to visitors. 15 Pine Rd, Orchards.

Park Station (1932)

Designed by Gordon Leith Park Station, built before the advent of air transport, was regarded as ‘the pinnacle of passenger transport in Africa’. Today a visit reveals only the functional modern edifice built for a post-gold rush city. The original structure housed the legendary glamorous Blue Room restaurant. The building was fitted with elephant head sculptures, Tuscan columns, grand vaulted concourses, fish ponds and custom-made ceramic tiles. While it remains locked off from public view, recent reports have it that the reopening of the Blue Room is being explored. De Villiers St, City Centre.

Anstey’s Building (1936)

Once housing a glamorous department store this 17-storey building which briefly was one of the city’s tallest, was designed by Emley & Williamson. With its zigzag profile and stepped outline it was one of the city’s most impressive Art Deco buildings and exemplified the optimism and worldliness of the age. Over the years it has been home to many colourful characters including the gay theatre director and member of the ANC’s armed wing, Cecil Williams who in 1959 was acquitted after being tried for treason. When Nelson Mandela was arrested in 1962, he was disguised as Williams’ driver. It is believed that Williams inspired the introduction of South Africa’s progressive laws on homosexuality brought into being by Mandela’s signing of the Constitution in 1994. Today Anstey’s is an apartment block. Rahima Moosa St, City Centre.

Anglo American Head Office (1939)

A monumental architectural work, this building was commissioned by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer from London architectural firm Burnet, Tait & Lorne. Duncan mentions the BBC Broadcasting House (1934) as one of its stylistic antecedents. Today it is still the African headquarters of Anglo American mining company. Occupying a full city block, the building is flanked by a pedestrian walkway that offers the perfect view of the imposing stone-faced exterior, ornate doors. 44 Main St, Marshalltown, City Centre

Heritage Tours

Many of the sites mentioned can be visited on tours with The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation, a non-profit organisation founded in 1985 dedicated to documenting and protecting the city’s heritage buildings. The foundation offers a regular programme of weekend tours and publishes a schedule at the start of each quarter. Tours are led by experts and visit many spaces that may otherwise be off-limits to the public. See the programme at joburgheritage.org.za/events.html. Tickets from Computicket (under the foundation’s former name Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust).

My Great Grandfather- Thomas Smith Tait was Lead Architect on the Anglo Building.

It has come full circle as I am a lighting design consultant and just completed the City of Johannesburg Council Chambers!

An amazing family legacy. The new building looks exceptional. A great addition to the city’s architecture.